Notes on a lecture by Broomberg and Chanarin

Main points:

They felt that the depiction of the 2008 Iran (Iraq?) war was very clean - with seeing, on a daily basis, a silhouetted soldier set against a desert background. Following that they got embedded into the British army fighting in Afghanistan not as photographic artists but as photojournalists for the Guardian newspaper. They described how it was that, through the photojournalists working at close quarters with the soldiers in the Falklands war , 'embedding' was adopted by the defence force. For the Afghan war they decided not to take a camera but just a box with 50m of light-sensitive paper in it. As part of their exhibition they had a film they made following this box from their studio in London, to Afghanistan & back to London.

They went deep into the theatre of war where, as journalists, the were expected to to report on what had happened , instead, they took out 6m of their paper, exposed it for 20 seconds and then rolled it up again whenever a soldier had told them to take a photo. It was a performative action against what they were seeing as 'a heroic depiction of the war'.

They thought it would be suspicious if they did not take a camera so they took a digital & took photos whenever they were told to do so. t the end of each day the soldier in charge of them would delete what he didn't like. At the end of each day B & C would delete everything they had taken. It was important for them to have gone back to their studio without any image. their photograms were a trace of a moment in time' Much like the ice samples which explorers drilled out of the north pole ice to see what had happened in its history - seeing the past through available evidence.

Their photograms are not figurative, not representational. The importance is the fact that the paper was there when the incident happened.

The work was seen as provocative to other photojournalists.

"They were interested in what people are looking for in images of suffering' and in what they are asking of a photojournalist.!!!

B & C were asked to judge images for the World Photo Awards. They gave the award to a photographer who was 3metres from the centre of the blast which killed Benazir Bhutto and who took the image - blurred and non-specific. The image had no other use than to testify that the photographer was there. B & C question how much information is needed in an image for it to function as a piece of evidence?"

Viewers look at their work and be confronted with the question "What do you expect to see from us - going as proxies on your behalf to witness these things?"

Incredibly relevant questions for us all to consider and particularly for me to consider for my project.

Channel 5 : Inside Strangeways Prison: 150 years.

I found the programme much more balanced than the Panorama documentary on HMP Northumberland covered below.

Some poignant facts:

* It was built in 1868 at a cost of £175,000 = £8million today.

* The name comes from the park & gardens it was built on.

* It has 10 wings, each with 4 floors and 80 cells on each floor and the layout resembles Jeremy Bentham's panopticon.

* In 1963 Women prisoners were held in I wing and death sentenced prisoners in B wing.

* It was built to house 964 prisoners & in April 1990, at the time of the riots, it had 16,470.

* There was a huge increase in numbers in 1945 & by 1947 it had gone from 15,000 to 40,000.

* The cells were 12' x 7' and were the minimum size in Victorian times for 1 prisoner. By 1990 there were cells with 3 prisoners.

* Celeb prisoners: 1961 David Dickinson (TV celeb)

2008 premier football league Joey Barton - released on good behaviour after 30 months.

2012 Dale Creagan who had already killed 2 people called 999 and set a trap to kill 2 police officers & then handed himself in to the police. He had served 4 years when he had created a gang of which he was the leader & so was moved around from prison to prison so that he cannot arrange gangs. = the 1074 = nickname for the merrygoround or the ghost train.

1998 Dr Harold Shipman arrested for killing 0ver 250 of his patients. Carried on a surgery in prison. He was moved to another prison where he committed suicide.

* The gallows hanged 100 people: 994 men & 6 women.

1964 the last hanging. 1969 the death penalty was abolished.

1951 - macabre record for the fastest hanging = 7 seconds.

Chief executioner - Albert Pierpoint who executed 12 prisoners.

* 1st April 1990: riot after the service in the chapel when the prison officers were overpowered & their keys taken which would open every gate and door in the prison. Alan Lord would break through the roof & start their revolt there.

A protest which was to last only a few days lasted 25 days & it would cost £55million to restore.

The prisoners' demands were not being heard because there was siren noise to drown their voices.

The editor of the Manchester Evening News, Mike Unger was asked to negotiate with the prisoners & he was to publish their message:

+ they were being treated like animals.

+ no more prison officer brutality.

+ no more slopping out

+ no more liquid kosh

* The rearrested prisoners were dispersed to other prisons where they sowed the seed of more rioting against the system.

All through the rioting, the media were broadcasting mis-information about what was going on inside the prison that there were kangaroo courts, that people had been killed & dismembered. While the prisoners were saying that there weren't & no reported deaths emerged from the investigations subsequently.

* 1994 Strangeways opened with a new entrance, new holding area and a new name: HMP Manchester.

There was a new staffing system in place whereby staff took on the roles of parents, teachers and other professionals. Their order & control was not to deepen punishment.

* 2015 the walls of the prison were breached by a drone bringing in drugs - synthetic legal highs which are impossible to detect. Within 3 years, there have been 58 prison deaths through drugs.

* Eric Allison (ex-inmate & journalist):"There is massive unrest in prisons today. It is dangerous for prisoners, dangerous for staff and dangerous for society. We are going to suffer in the future."

* Ex-warden: " If prisoners are seeing so much violence in prisons , when they go out they are not going to change. They are going to go out no better than when they go in."

Head of production: Maureen MacPhee

Noel Smith: ex-inmate & journalist.

Some questions it raised for me:

So much research has been carried out on psychopaths who have been admitted to jails as criminals who could not empathise with their victims. I was wondering if anybody carried out the same tests on the hangmen. How could they , in cold blood, hang a fellow human being if they are 'normal' members of the public? Or did they not see them as human beings but, like the psychopaths, saw them as 'cardboard cutouts'?

If 'we' see the prisoners as a conglomerate 'them' , do we know who / what we are?

What /Whom is a prison for?

Have we reached a new watershed in how we deal with enmity?

Liza Factor

Includes a difference between 'multimedia' and 'transmedia':

Multimedia = literally a combination of media -text, audio, images etc.

Transmedia = telling a story across multiple platforms and specifically splitting the narrative between platforms usually involving digital technologies.

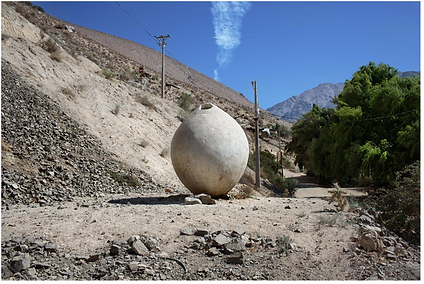

In 'Ball & Flint: transmedia in 90 seconds' (2013), Pont likens transmedia story-telling to "throwing a piece of flint at an old stone wall" and "delighting in the ricochet", making story something you can now "be hit by and cut by".(Transmedia on Wikipedia)

Using Transmedia storytelling as a pedagogical tool, wherein students interact with platforms, such as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or Tumblr permits students' viewpoints, experiences, and resources to establish a shared collective intelligence that is enticing, engaging, and immersive, catching the millennial learners' attention, ensuring learners a stake in the experience. (idem)

Transmedia theory, applied to a movie launch, is all about promoting the story, not the 'due date of a movie starring...' In an industry built on the conventions of 'stars sell movies', where their name sits above the film's title, transmedia thinking is anti-conventional and boldly purist. (idem)

Donovan Wylie

This is another photographer and work recommended by my CS tutor, in keeping with my interest in identity, and its removal by structures in the penal code in the UK .

What I appreciated most from this work is the consistent approach to presentation. The palette is uniform, almost to the point of being a mesmerising monochrome. Was I seeing the same image many times over? No. The differences, being almost imperceptible, are disorientating: I found myself having to look closely at the images to see how they were different.

In Louise Purbrick's essay 'The Architecture of Containment' in the Maze books, I found the following points of interest:

"Repetition is a feature of control systems. The duplication of physical structures (walls, cells, blocks) produces a predictable environment allowing security to be planned out and then constantly repeated. The H-blocks are distinguished by the numbers one to eight; otherwise they are the same remorselessly functional structures.'(p4). Of course, this is not the only feature of the control and security systems in place: how a prison is governed also has an effect on its security.

In looking at public, state or private institutions like prisons, hospitals, schools and police stations, this repetition and duplication is very evident and, when you consider that control systems in such institutions is one of their mainstays, expected. I did not, however, expect it to be so evident in hotels where I had thought that there was not the same need to control but where security is important. Other factors must therefore be determining that repetition.

There is the need to construct those institutions as economically as possible. Repetition, therefore, is important: 'repeating rectangular cell-units was evident in England in the 1970s. Work began on Channings Wood in Devon in 1972, on Deerbolt, County Durham in 1973, and Featherstone in Staffordshire opened in 1976, the same year as the H-blocks." (1:p 11)

The design of the pre-fabricated low-rise cubic structures made up into H-block groups or clusters of cells creating smaller units of prisoners had been constructed some twenty years earlier in the USA in the rebuilding of the notorious State Penitentiary at Angola. The new prison design was praised by the architectural press for its economical design. In the 1961 issue of The British Journal of Criminology it was stressed how the prefabrication kept costs per inmate to 'an extremely low figure'.(1:p.11)

One of the advantages of the H-block system was that it reduced the density of the concentration of prisoners as seen in 19th C jails which follows the courtyard, radial structure as seen in the museum of Bodmin jail. There was an attempt in the 20th C. to mimic a campus style prison structure which also recreated a more human scale environment and, as a result, an easier way to control: a divide and rule strategy.

The tone of the essay reveals a frustration that the author has with the political structures and rationales of the British authorities, which refused to allow that there was a difference between political and criminal prisoners. The Maze was exclusively for political prisoners, both loyalists and republicans. Prison rules regarding discipline offences were enforced and republican prisoners stated that they were enforced 'with brutality' and that their reaction was to withdraw any co-operation. (p16) A 1978 report by Archbishop Tomas O'Fiaich after he had visited the Maze is quite revealing of the conditions in the cells he saw:

"The stench and filth in some cells, with the remains of rotten food and human excreta scattered around the walls, was almost unbearable. In two of themI was unable to speak for fear of vomiting. the prisoners' cells are without beds, chairs or tables. They sleep on mattresses on the floor and in some cases I noticed that these are quite wet. they have no covering except for a towel or blanket, no books, newspapers or reading material except the Bible (even religious magazines have been banned since my last visit); no pens or writing material, no TV or radio, no hobbies or handicrafts, no exercise or recreation. they are locked in their cells for almost the whole of everyday and some of them have been in this condition for more than a year and a half." (1:pp 16-17)

The images presented by Wylie in Maze 1 reflects none of that. He took them after the whole philosophical and concrete realities had run their course. There is a certain peace around the Inertias, the Steriles and the Roads. In his description, Wylie states: "If you walk from the perimeter wall towards the centre of the prison, as if breaking into the prison from the outside, it becomes clear how inertias lead to sterile, and sterile lead to roads that lead to the blocks. The pattern of such a journey is one of constant, relentless repetition on a vast scale. This sense of repetition is intensified once inside the block ." (The Maze 1 introduction) Images of the made-up beds in the cells, with the curtains on the windows and their concrete bars reducing what could be seen at ground level, restore a human peace to the tumultuous events which led to the closure of that structure of control and isolation.

The Panorama programme recently revealed the lawlessness in HMP Northumberland. What annoyed me most about that programme was its bias. Because the recent press coverage of prisons in the UK has painted a uniformly black image of their state of affairs, it would have been good to have seen, even for a short while, a prison in which this was not the case, like HMP Dartmoor, for example, which, according to my sources, rarely has violent eruptions. But no, we were given more of the same violence and non-conformity. It begs the question :in what way do the prisoners benefit from being there?

My screen grab of the iPlayer version of the recent Panorama undercover report on HMP Northumberland.

Ironically, the cleaned-up system was being dismantled in Maze 11, separating the concrete from its re-inforcing metal rods; collecting the wire fences; everything stripped down to its bare essentials. "Layer after layer of fencing was folded and piled neatly, then delicately carried away. The crushing machine, 'the muncher' (designed to the specifications of the head of a tyrannosaurus rex), gnawed through the internal walls and prison cells." (Epilogue to Maze 11). The reverence and care which seemed so alien to the establishment when it was inhabited, is overpoweringly present in these images of returning dust to dust, making certain that no trace of suffering and control is left anywhere. Nature is not allowed to take over this bastion of control and isolation as it has done in so many prisons elsewhere. Wylie's concluding sentences explain how he felt about the whole demolition: "As each layer fell one had the sense of getting closer to something, and the falling of each layer became, for me, a moment to contemplate why all of this happened. But the further one penetrated, the less seemed to be revealed, as if there were no answers at all." (Maze 11 epilogue.)

The other extreme is the work, undertaken over 10 years, by Valerio Bispuri who recorded his experiences in 74 prisons throughout Latin America including Lurigrancho in Lima, Peru, which holds ten thousand inmates: a city within a city. Bispuri maintains that his work is not about prisons but about lost freedom and lack of choice. His images are gritty, black and white and at times, look as though they were taken on-the-run. Their cohesion conveys the impression that it does not matter where the images were taken, the circumstances are all the same.

He states " I have always believed that photography's difficulty, but also its power, lies in the ability to balance your own emotions with reality. And only once you have succeeded in calibrating your own profound emotions in a real concept without one prevailing over the other it is possible to tell a story. Only at the moment in which I have managed to be in contact with what I am feeling I do (sic) take the shot.'(P. 12)

Bispuri's prisons teem with people who are condemned, both guards and prisoners. He was struck by the low levels of suicides compared to the prisons in Europe or America. In one of his reportages, he covered the most notorious Pavillion 5 of the Argentine Mendoza prison. What emerged was 'a massacre, a disgrace, emblem, evidence of inhumanity, not of the prisoners, but of the State instead.' (P. 9) Following the publications of the images, Pavillion 5 was closed because ' when you recognise yourself in another person, the worst person possible, perhaps you manage to comprehend that his humiliation .'(p. 9)

'Prisons are a reflection of society, a mirror of what is happening in a country, from small dramas to the great social and economic crises. The prison is a community, a non-place where nevertheless people live each day with precise rhythms and spaces (p. 11)

Both photographers reference people; both reference the philosophy of control and containment; both make you feel their presence but in two very different ways. They both use light effectively to suit their purposes. My screen grab of the Panorama programme reflects the predominant coverage of the pitiful state of current media reporting in the UK press, in my opinion.

It is this everyday banality, reflected also in letters to me from a friend in prison, which interests me. There is no doubt that violence exists in many prisons on both sides of the Atlantic but the difference in the way it is covered by different photographers is worth investigating.

References:

Bispuri, V.: 2014. Encerrados. Contrasto srl. Roma.

Wylie, D.: 2016. Maze. Steidl.

Panorama programme on HMP Northumberland.

Experimenting with structure

MARCH 21, 2017 / 2 COMMENTS / EDIT

I recently had to submit my first assignment for both modules. The essay was relatively simple – but it had to be researched and done. The BoW assignment requirements I had read right at the start of the course and promptly forgot the details. Consequently, I got myself into a huge muddle and, subconsciously, started making my final piece! Only on reading the brief the day before submission did I realise I just had to find 30 images from one shoot.

This is what I had sweated over in the 10 days before submission:

Men behind bars 1 with plain background

Men behind bars 2 with the images taking up all the space

Men behind bars 3 with motherboard background

It was all very confusing and confused and not sending any message across. I was emulating the work of Jeremy Gardiner which I referenced in a previous blog:

I then decided to pare it all down and tried to continue with the bars idea but combine it this time with the architectural structure of the prison & hotel:

Trying to emulate the idea of architectural perspective with the prison bars. Each column is made up of the screen grabs from the Panorama programme on top of the letters.

The first arrangement of perspective.

I found both ideas too literal and it was at this point that I went to read the instructions… when all else fails …

Bodmin jail 2017

“Bodmin Goal – a Milestone in Prison Design”(P19)

What struck me immediately on entering the town museum, was that you had to go through the cafe and shop. The entrance fee was quite expensive, £8.50 with a student concession but the coffee was good.

The museum experience is divided in to two sections: those which have been refurbished and those which have not. The refurbished section is limited to the wing which starts at the entrance and stretches from behind the façade to the end of the reception cells.

The the ground floor is labeled as ‘reception cells’ in the museum map and was the place where prisoners were held before they were allocated to their permanent cells. Why do the rooms have to have coloured lights shining on them? Is this the Disneyfication simulation treatment which has entertainment as its primary goal? if, through our Red Arrows displays we can make warfare entertaining, why not make the suffering of hundreds of men, women and children entertaining too?

I never managed to decode the colours' significance beyond their entertainment values.

There were tableaux morts in all the cells and service rooms:

From the refurbished and un-refurbished parts, the windows gave me an idea of what the prisoners could see

In 1911 the female part of the jail was closed.

In 1915 the male part of the jail was closed because there were so few prisoners.

In 1922 the naval prison was closed.

In 1927 Bodmin jail was formally closed.

In 1920, the first telephone kiosk (K1) was introduced by the United Kingdom Post office in concrete painted white with red trim.

In 1924 after a design competition won by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, a red telephone kiosk (K2) inspired by the mausoleum of Sir John Soane, was manufactured like these in Covent Garden.

The jail was closed in 1927 so, if the installation of the kiosk at the jail is to be valued historically, the authorities must have had special dispensation to have this one placed here so quickly. Four more design variations of the kiosk were to be produced over the subsequent eight years.

Prison is a physical place, isn’t it?

FEBRUARY 12, 2017 / 2 COMMENTS / EDIT

The first time I stepped in to a prison was ten years ago, I think – I cannot exactly pinpoint the year – and the visit left such a permanent mark on my consciousness that I had to ask myself “What were you expecting when you went in?” The answer must be that I had a preconceived idea of what prisoners looked like – they all wore grey and black uniforms? they probably had scars on their faces? they had a particular gait? always grumpy? self-assured? threatening? in the Crime Watch programme they all looked the same – stubble on their faces, unkempt … Those preconceptions were formed by visual representations I had seen in films, newspapers and television – I had never actually known anybody who had gone to prison so I had no counter-impression, no different idea.

And then there was Jim (not his real name). I knew what he looked like. He had none of the features I was expecting to see.

I went to visit Jim, a member of our congregation who had been sentenced to 12 months in prison for sexually assaulting a young man with learning difficulties. As soon as all the clanging of gates, chains and steel doors had stopped and I was sitting opposite Jim, I looked around me. The prison Chaplin was sitting in the same room and with his back to us – for my safety? to hear what I was saying? I did not ask because it did not seem appropriate and because I was stunned at what I saw: men (this was the men’s wing), walking freely along the walkways wearing T shirts and jeans: it looked like an ordinary institution in which the people wore casual clothes. There was wire mesh under the walkways and between them across the width of the building so that if anybody fell off the walkways they would not get hurt – that was not ordinary. Everything else seemed so ordinary. The people all looked so ordinary. I asked about the jeans and T shirts and was told this was the uniform. They were relaxed. There were no raised voices. There was no swearing. The men I saw were mostly in their 20s and 30s. They smiled and seemed to be talking affably with one another. They seemed free to move about. Nobody was swaggering. They were just ordinary people. The walkways could have been pavements in a street anywhere or walkways in a shopping mall.

My visit over, I walked out, collected my handbag at the external gate and went in to the street where I saw very ordinary people in jeans and T shirts ( it was summer) walking freely, talking affably to one another, and they were mostly in their 20s and 30s. I was near the university.

This experience made me think about how we often form opinions of people merely by looking at them: any one of the people I saw in the streets after my visit could be a murderer, rapist, felon … they just hadn’t been caught. The opposite is, of course, also true: so many people we see have done amazing thing for their neighbours but they don’t have it emblazoned on their chests!

So I decided to start taking photographs of people in the street to see how I would react to them. The images in the first set were all taken with my iPhone in Exeter along the canal. I have assiduously avoided people in my images so far because I have a ‘thing’ about photographing people – so part of the reason for focusing on identity is to overcome this aversion.

This set of images was taken mid-week, in a recreation area and during office hours, which explains why the composition of the subjects is limited to pensioners, mostly. I did not ask if I could take their photo.

I have no idea who these subjects are, but the question as to whether or not they are criminals, still pops in to my mind, certainly not as often now as it did on that day when I stepped out of prison.

The salutary lesson I learned is not to classify people, let alone to classify them according to where they find themselves – I knew that before my prison visit, but I did not realise how much I did that.

Prison is a physical place, isn’t it?

If I am to see people for who they are, I need to look below the surface – see what they write, for example.

I shall continue to take random images of people outside institutions just to see if my impressions are prejudicial, for the time being.

I have no idea where this project will take me.

More images which can make some of us question the status of people:

“Chaos in one of the biggest prisons in the country has been revealed in secret filming for the BBC.”(1)

FEBRUARY 17, 2017 / 2 COMMENTS / EDIT

” An undercover reporter spent two months at HMP Northumberland, which houses up to 1,348 male inmates, for Panorama.

“He discovered widespread drug use, a lack of control, door alarms that did not go off in one block and a hole in an internal security fence.”(1)

There is so much coverage in the press of the state of prisons, prison staff and prisoners, that to get any semblance of a balanced picture of the true state of affairs seems almost impossible. Is the state of HMP Northumberland typical of the state of prisons nationally? Are there no prisons in which the prisoners are not in charge, in which drug taking is not rampant and in which state cut-backs have meant that there are not enough prison guards?

Last Monday night I had other commitments so I watched the Panorama programme on iPlayer. As so often happens, the image on the screen was badly pixelated at the base but it seemed, in a bizarre way, to reflect the chaos which was being reported in the programme. I took screen grabs with my phone of the parts I thought best reflected that chaos and also feelings of imminent disintegration:

“the Conservative MP and former prisons minister Crispin Blunt, … said: “We have got to get to a place where prison is used as a place to turn people around.”” (1)

References

‘Undefined photography’ with Jan Cieslikiewicz

FEBRUARY 19, 2017 / LEAVE A COMMENT / EDIT

“Mostly the mystery, and the absurd. Ideally some combination of the two. I will make a bold statement; the world and life make absolutely no sense.”(1)

This is the response Jan gave to the question what his photography is about. In another interview he said that, after having spent many years in the world of maths, figures and ‘truth’ (in maths) , he was longing for something undefined.

In photography, in that ‘single visual word’, he finds that ‘undefined’ through ambiguity, contradictions and multiple emotions: he wants to feel the world’s beauty without thinking. He wants viewers to ask all the W questions about his work: when, where, what the hell is this?

Jan has left the world where beauty is in the abstract science of maths and has gone to find it intuitively in an indeterminate and undefined visual experience. Perhaps because it was an aesthetic imposed on him by his mathematician father, but why couldn’t he see that beauty and balance in algebra? In mathematical theory? Possibly because he wanted to live, I suppose, and experience the serendipity of an un-calculated life which made him ask questions to which there are no answers and in which relationships are random and uncertain.

Is the secret of photography for him to find those images which do that?

The images below are part of his series ‘Null hypothesis’ which he explains on his website:

‘“Null hypothesis” refers to one of the most important analytical research methods used across a variety of fields, from psychology to physics. In null hypothesis testing it is usually presumed that given observations result purely from chance, whereas the alternative implies influence by a non-random cause. The aim of this method is to reject the null hypothesis, and thus prove—with certainty beyond reasonable doubt—that the random explanation is false, and the hypothesized non-random one is true.’ (2)

Images are presented here with the kind permission of the author.

How and why is this relevant to my proposed project?

‘The world and life make absolutely no sense.’

I have many questions on issues concerning prisons and identities which are the main strands which, at this early stage of my project, guide my thinking:

The whole incarceration system makes no sense to me.

What being is supposed to emerge at the end of his/her stay in a prison? A reformed one? A conforming one? A rehabilitated one? A penitent one? A changed one? An educated one? I am hoping that my Goffman reading will help me with that.

Who determines what determines the relationship between prisoners and staff ?

A non-answer may lie in a statement by Cieslikiewicz himself:

‘From every day events to the most fundamental questions, both on a personal and cosmic scale, we are surrounded by contradictions, unknowns, and change’ (2)

References

Jennifer Wicks & Assaf Shoshan

FEBRUARY 20, 2017 / 4 COMMENTS / EDIT

Although my research is intended to be wider than prison systems , I have found so much information on the internet concerning photographic artists who have undertaken prison studies that I cannot ignore some of them.

The work of Jennifer Wicks is “primarily concerned with people and their environment, with particular interest in how our communities can determine who we become. … she explored key components surrounding the notion of ‘them and us.” (1)

Wicks did her research during a residency with the Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research at Glasgow University.

Her work, presented in April 2013, focused on the mug shot: how it was used in Victorian times, and how she chose to subvert the intentions behind its use in contemporary society. Sharon Boothroyd, the interviewer, asked what interested Wicks most about the mug shot, since it was used traditionally as ‘ a stark portrait, void of emotion, intended to reproduce accuracy of facial features and be a source of recognition. ‘ (1) Wicks’s interest lay in looking at how, this icon in contemporary visual culture, set a benchmark in how the pose and the framing are accepted to imply an element of criminality in the sitter. The mug shot represents a visual display of power relations not only between institution authorities and the sitter but also between the viewer and the sitter – the implication that the sitter is already culpable and in which:

‘that judgment is recorded, stored for future viewing separate of context and history, somewhere where the subject cannot defend themselves; the accused, not yet officially convicted.'(1)

She claims: ‘You connect with people differently through eye contact, even in a photograph. I’m deliberately taking emotion away from the portrait and by concealing visual clues I’m also concealing the sitter’s identity and challenging people’s assumptions. This juxtaposes and upsets the meaning of the police mug shot.'(1)

Not only does this posing upset the traditional clues in a mug shot, it also gives the sitter a certain vulnerability, which we all have. Wicks also claims that police mug shots strip away all the complexities of a sitter and they become part of a subset. Furthermore, Wicks also claims that in black and white rather than in colour, the sitter becomes an object whose particular features need to be captured and resonate with our deep-seated impressions of convicts as presented by the media and sensationalist reporting.

The technical process of the project was complex involving, inter alia, the use of Polaroid films which is something I know nothing about but which I would like to investigate for use in this project. ‘She describes the extraction of the negative image as “unstable, messy and laborious” but feels the visual counterpoints of Polaroid negative images add “an ethereal element” to her body of work. “I have essentially produced two quite different pieces of work at the same time,” ‘ (2).

Wicks was asked if this residency had changed her notions of punishment. The reply was that it had challenged her ‘everyday’ sense of punishment and that she was sure not many of us understand it fully possibly because the prison system is sensationalised and misrepresented ‘beyond belief’. Her final quote:

‘People aren’t born bad, life experiences and society make them bad. The system that f**** people up is also there to punish and that doesn’t feel right to me.’ (1)

Assaf Shoshan presented fifteen photographs taken in 2014 that are part of the project, Peines Partagées (shared punishments) he developed during his residency, dedicated to Roman prison Rebibbia inmates and their companions. The three images available show people standing in what appear to be prison corridors. The images appear to be taken from short videos of the people who are standing in the same place but moving their heads slightly. As with Wicks’s work, you are left to wonder if they really are prisoners, or perhaps they are prison staff out of uniform or people in the prison in other professional capacities. There is, sadly, very little online information on the author and work.

There are several ideas I get from these readings:

a. Try out some polaroids.

b. Think about how to pose sitters: ‘mug shots’ or 3/4 portraits and short film clips?

c. How do I ‘layer’ images to create composite ‘mug shots’?

d. Try to combine architecture shots with portraits.

References

1. http://www.photomonitor.co.uk/us-and-them/

2. https://prisonphotography.org/tag/they-are-us-and-we-are-them/

Jeremy Gardiner painter and collage artist

FEBRUARY 20, 2017 / LEAVE A COMMENT / EDIT

Several years ago, I saw an exhibition of paintings by Dorset based Jeremy Gardiner which drew me in but I do not know why. I feel that using a combination of montage and collage makes me consider the different layers which constitute a person’s make up. How some shapes overlap others thereby hiding parts of the shapes is also important: the hidden influences which have made us what we are and which we may want to hide but which are felt. In Gardiner’s work, they are evocations of place – but our own personal landscapes are made of layers of experiences and choices, with some being more obvious than others.

DAY: FEBRUARY 21, 2017

Sol LeWitt inspiration.

FEBRUARY 21, 2017 / LEAVE A COMMENT / EDIT

Why can’t we all have a Sol LeWitt in our lives? … and a BC as well – it goes without saying!

Parts of his letter to Eva Hesse are good for many of us to hear as we struggle to get inspired. Benedict Cumberbatch reads the letter here with all the drama and insights imaginable and sufficient to make anyone get up and DO!

“Stop thinking, worrying, looking over your shoulder, wondering, doubting, fearing, hurting. Hoping for some easy way out … and just DO.”

The relevance to my project lies not only in the advice given, but also in that Benedict is reading a letter, and letters are at the heart of this project. My letters are in no way as dramatic as this one but they are letters nonetheless.

Identity in nature

FEBRUARY 21, 2017 / LEAVE A COMMENT / EDIT

My walk along the River Tone on Saturday made me think about how we can be seen in the natural world immediately around us.

In 2015, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs passed a law making it illegal for shops with 250 employees or more to issue free plastic shopping bags. The 5p charge was not a tax but it was left to the individual shops to donate the money to their good cause of choice.

The statistical evidence given for the introduction of the law was: “In 2014 over 7.6 billion single-use plastic bags were given to customers by major supermarkets in England. That’s something like 140 bags per person, the equivalent of about 61,000 tonnes in total.” (1) Such clear evidence in support of the law suggests that something had to be done. The effects were immediately seen – no longer did we see plastic bags floating in the winds or littering our pavements. Fewer of us saw the effects in the oceans.

The benefits are listed as:

“We estimate that over the next 10 years the benefits of the scheme will include:

-

an expected overall benefit of over £780 million to the UK economy

-

up to £730 million raised for good causes

-

£60 million savings in litter clean-up costs

-

carbon savings of £13 million” (1)

The third point interests me: £6million saved each year on litter clean-up costs. Where will that money be spent? As we can see around us, it has not been spent on clearing up litter which still colours / reflects our values in our streets and cities.

In the six months “from 5 October 2015 to 6 April 2016. These initial results indicate that over this 6 month period:

-

at least £29.2 million was donated to good causes – environment, education, health, arts, charity or voluntary organisations, heritage and sports as well as local causes chosen by customers or staff

-

there was a very substantial fall in the number of single-use carrier bags used” (1)

An interesting but irrelevant (up to a point) aside: If the figures are to be believed, the expected benefit to charities over the year were expected to be £73million, therefore in half that time they would expect to get about £36 but only got ‘at least £29.2million. Extrapolate that figure to the expected 10 years’ forecast: instead of the £730million we would have donated only £584million = a shortfall / leak of £146million. Obviously some people are still buying new plastic bags. Where is the rest of the money going? Are people still using one-off plastic bags? Not as evidenced in our stroll along the Tone.

Identity in this blog will be reflected by snapshots taken with my phone of what I observed on my walk. The area, in the middle of Taunton and was being used by families as well as by individuals on what was a brilliantly sunny, early Spring, Saturday afternoon in late February. The images are fragments of interactions between man and nature in this one small town in the South West. These images are not intended to pass judgement on the place, it is what I perceived and recorded the area I passed through for the first time. They do not pass judgement on how the area is used either.

Stephen Poliakoff: Shooting the Past released in February 2004.

-

Writer & Director: Stephen Poliakoff

-

Producers: Helen Flint, John Chapman, Peter Fincham, Simon Curtis

From the description on the Amazon site:

Winner of the Prix Italia.

Starring Lindsay Duncan, Timothy Spall, Liam Cunningham, Billie Whitelaw, Emilia Fox, Arj Baker and Blake Ritson.

Plot: As the representative of a US corporation, Christopher Anderson is developing a country house on the outskirts of London into a business school for the 21st century, which would be fine … if it were not the home of a unique photographic collection, cared for by a small but determined staff.

DVD 1 has the writer & producer Poliakoff speaking over the action about how the film was made on a very limited budget and how he & the producers arranged and rearranged the rooms for different scenes. It sounds like they had a fun time making it & how talented the actors are, which becomes very evident in the 2nd DVD when you see part 3 of the film without over speakers or subtitles. The action is tense and you never know, like the character Anderson, what is coming up next. The suspense is enthralling as is the dark theme carried by the limited lighting on the set.

James Russell Cant: Divided to the Ocean 2009

Taken from Cant's website, elements in the following text can apply to my prison project too:

D:C.2.6 concerns an individual's relationship to time and place, as does almost everything ever recorded. This individual is a prisoner, the time is a sentence, and the place is a prison. The subject and images in D:C.2.6. can be seen literally or as a metaphor for a process leading to redemption: as successive layers of freedom, restriction and a dreamed-of freedom of movement, of contact and of expression are simultaneously conflated and separate. Some of the images are therefore palimpsests of response and echoes made through correspondence over a calendar year, which underline how places and experiences are both separate yet conjoined by time. The individual can, of course, also be the author who, over time, falls prey to misinformation and prejudice and who also, by scratching away at her memory and mindset, seeks redemption.

“Behind all seen things lies something vaster; everything is but a path, a portal or a window opening on something other than iteself. ”

― Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Wind, Sand and Stars

The quote from Wind, sand and stars fits in with The Little Prince because both books are about perceptions. In the latter, the Prince wants the crash-landed aviator to draw him a sheep and the only sheep the prince will accept is the one he can't see - it's in a box the aviator has drawn.

I am going to use the paradigm of the Little Prince's planet as my model for my project and I am going to devise an app to convey my concept of there not being just one depiction of prison life. I can't get into a prison so I am not only photographing the unseen, but also leading the viewer along various paths, through different doors and up to windows which frame different views of life which transcends prison walls.